Noise 101

Video capsule: Noise 101

In this first capsule of a series of three videos, Manon Robin, community relations manager, explains why noise is a much more complex subject than it seems.

Why do we say that noise will be similar based on infrastructure and track configuration? Well, it’s all down to the behaviour of noise and its properties.

What is noise?

Scientifically speaking, sound is energy produced by vibrations that spread through air, water and solid materials in the form of waves. It can be divided into three categories: audible sound, infrasound and ultrasound, not all of which are perceptible to the humans.

Noise perception therefore varies from one environment to another, as well as from one person to another, depending on age and sensitivity. However, there is a way to assess this objectively.

How is it measured?

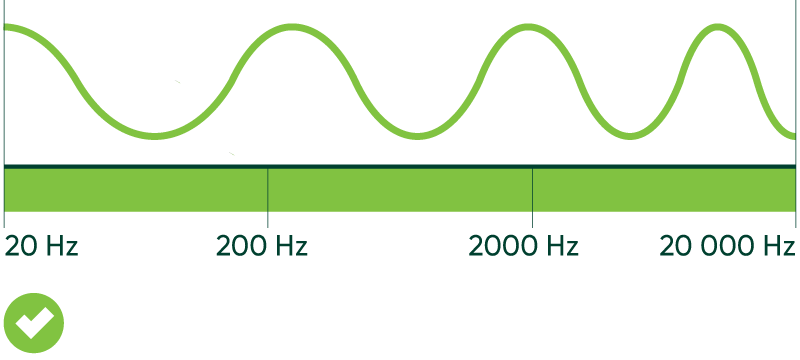

The frequency of a wave (the number of times it is repeated in a second) determines what our ears perceive. The human ear generally picks up midrange frequencies.

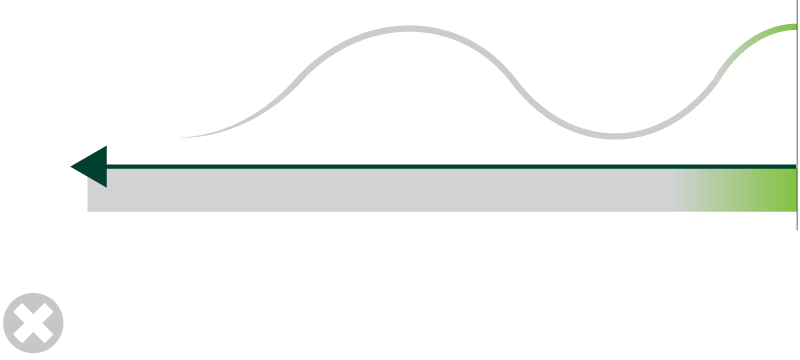

Low frequencies or infrasound

Too low to be heard

Midrange frequencies

Sounds that are audible to humans

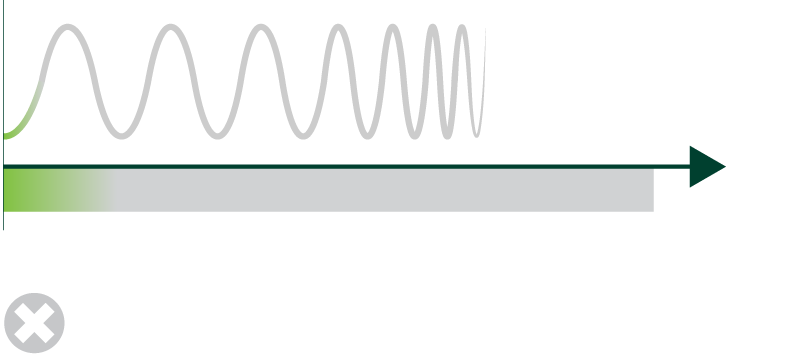

High frequencies or ultrasound

Too high to be heard

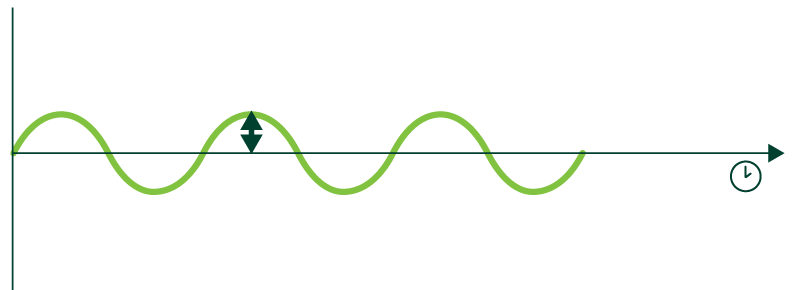

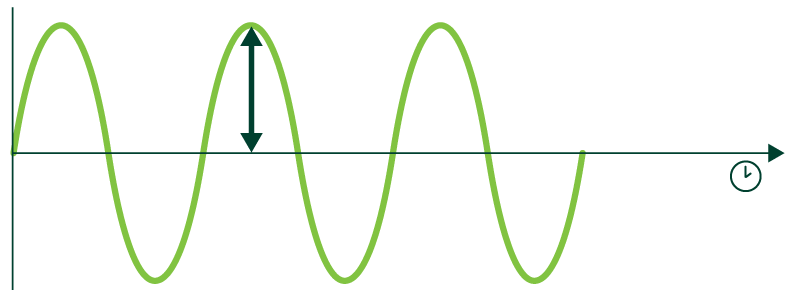

Additionally, the amplitude (size) of the waves determine the sound levels. The greater the amplitude, the louder the sound.

Soft

Loud

The unit used to measure it is the decibel (dB). However, in order to paint a true and objective picture of the situation, A-weighted decibels – dB(A) are used in acoustics to describe how a sound is perceived by a human being.

To better understand how this translates into our environment, a scale of sound levels generally present in an urban area has been created:

| 0 dB(A) | 20 dB(A) | 40 dB(A) | 60 dB(A) | 80 dB(A) | 100 dB(A) | 120 dB(A) | 140 dB(A) |

| Silence (Threshold of hearing) | Strong sense of calm | Peaceful | Quiet conversation | Strained conversation | Tolerable | Unpleasant | Unbearable |

Known sounds in our environment and the level of dB(A) produced

The sound level meter is the tool used to measure decibel levels. This device has a microphone that measures the number of particles in the air that are “displaced” and which we perceive as sound. These particles are then converted into decibels.

Standards exist to make sure that noise measurements are representative of reality. As such, the sound level meter is placed close to the noise source you want to assess: this is called measuring noise at source. As a result, the measurement will be less polluted by other surrounding noises.

Also, the further you move away from the noise source, the more it blends in with the existing environment and the less perceptible it becomes. However, other factors can influence sound waves and make them react differently, such as the presence of physical obstacles (walls, houses), weather conditions (snow, rain, wind), or the presence of water bodies (rivers, lakes). It can bounce, be deflected in several directions, transmitted, absorbed or even cancelled itself out. It all depends on the obstacles it meets and the configuration of the space.

In the case of the REM, different track configurations also affect the noise emitted by passing cars. Some are specific to the South Shore sector, others to the Deux-Montagnes and Anse-à-l’Orme sectors.

- Track configurations in the Deux-Montagnes and Laval sectors

- Track configurations in the Pierrefonds-Roxboro and West Island sectors

- Track configurations in the Saint-Laurent, Ahuntsic-Cartierville and Town of Mont Royal sectors

The noise analyses to be carried out at source between the Saint-Eustache maintenance yard and Sainte-Dorothée station will measure the decibel level generated by REM traffic throughout the Deux-Montagnes and Anse-à-l’Orme branches, which share the same track characteristics.