Archaeological discoveries in Pointe-Saint-Charles

In November 2019, archaeologists found bone fragments at a REM construction site in Pointe-Saint-Charles. This discovery confirmed the existence of a cemetery where 6,000 Irish immigrants were buried in 1847. Here is a look back at this little-known history of Montréal.

Montréal and its Irish heritage

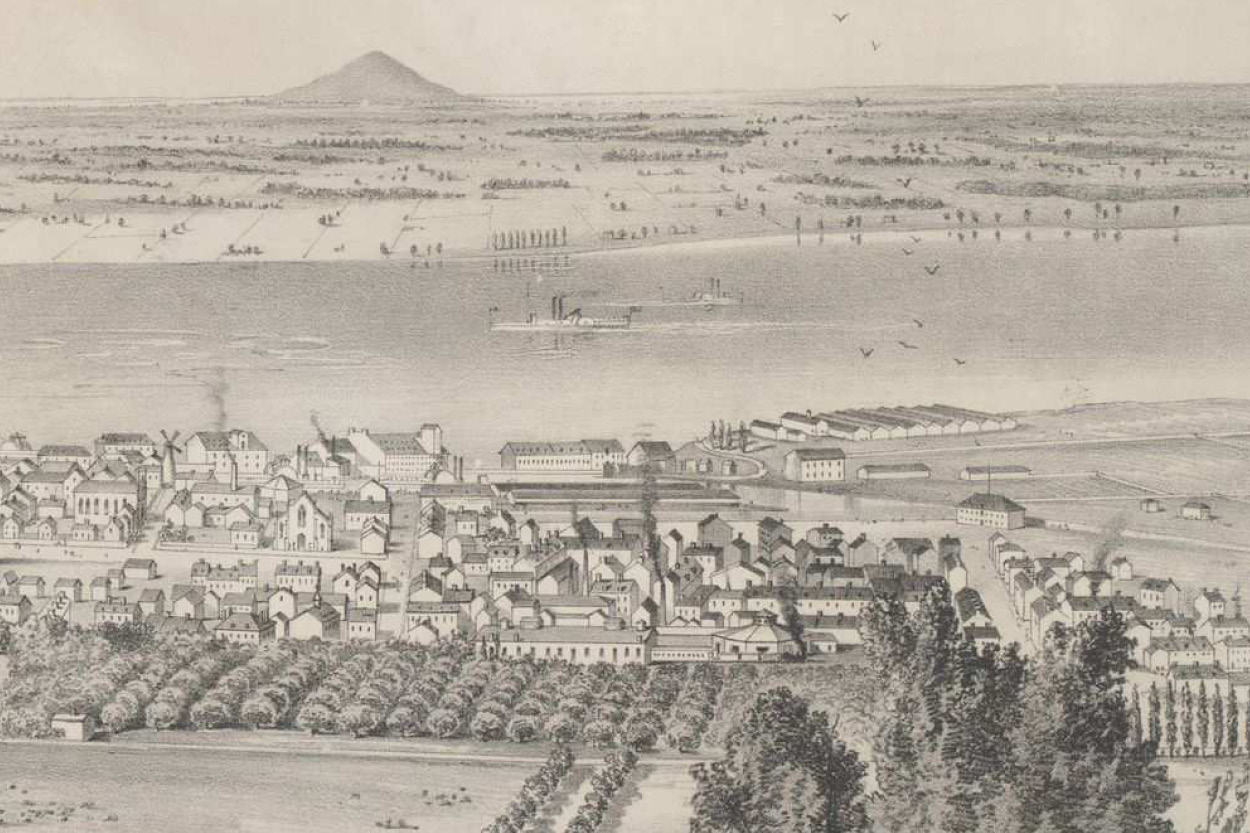

The first Irish immigrants arrived in Canada in the 17th century to try their luck in the “New World.” Irish immigration reached its peak between 1810 and 1830. Tens of thousands of newcomers settled in the working-class neighbourhoods of Griffintown, Pointe-Saint-Charles and Victoriatown.

View of the southwest from Mount Royal. Endicott and Co., McGill University Rare Books and Special Collections, 1852

View of the southwest from Mount Royal. Endicott and Co., McGill University Rare Books and Special Collections, 1852

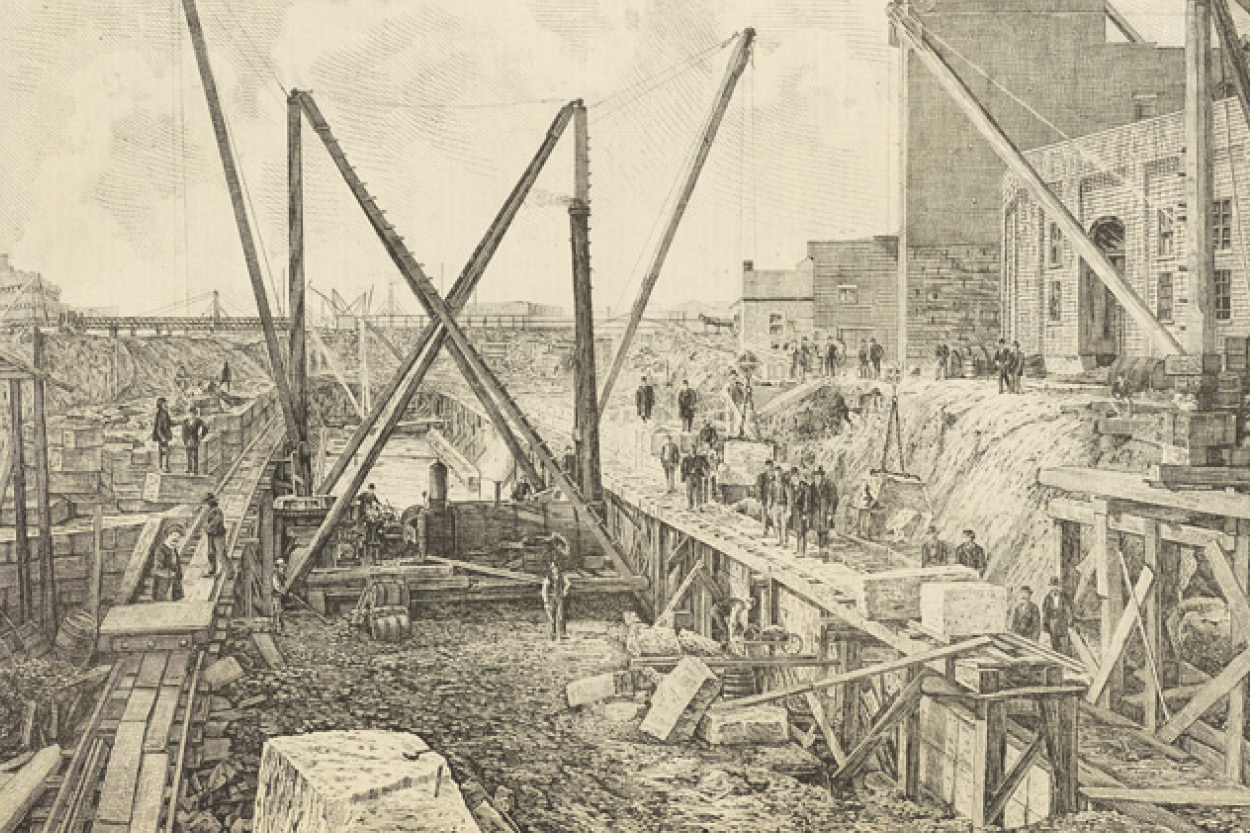

The Irish contributed significantly to the city’s development. They took part in all the major projects of the time, such as the Lachine Canal (1825), its extensions (1843, 1875) and the Victoria Bridge (1854). Working under difficult conditions, they also participated in the development of unions. Iconic sites such as the Joe Beef Tavern (1875), which served as a meeting place for workers, illustrates the Irish community’s influence in the city.

Widening the Lachine Canal at the Saint Gabriel locks. Canadian Illustrated News, 1877

Widening the Lachine Canal at the Saint Gabriel locks. Canadian Illustrated News, 1877

In the 19th century, the Irish were the second-largest ethnic group in Montréal. In fact, the city’s coat of arms has displayed the Irish shamrock since 1833, in recognition of Irish immigrants as one of the city’s founding people.

The typhus epidemic of 1847

History took a tragic turn in the middle of the century. The Irish fled their country due to the lack of food that hit Ireland during the Great Famine (1845–1852). Packed into ships under unhealthy conditions, many travellers came down with typhus, a deadly fever transmitted by insects living on rodents.

In 1847, thousands of Irish immigrants arrived by boat and were quarantined on Grosse Île, near Québec City, before continuing on to Montréal. Despite the quarantine, travellers carrying the bacteria arrived in Montréal and an epidemic broke out: more than 6,000 Irish people died of typhus, in addition to 1,000 residents and even the mayor at the time, John Easton Mills, who had visited the sick.

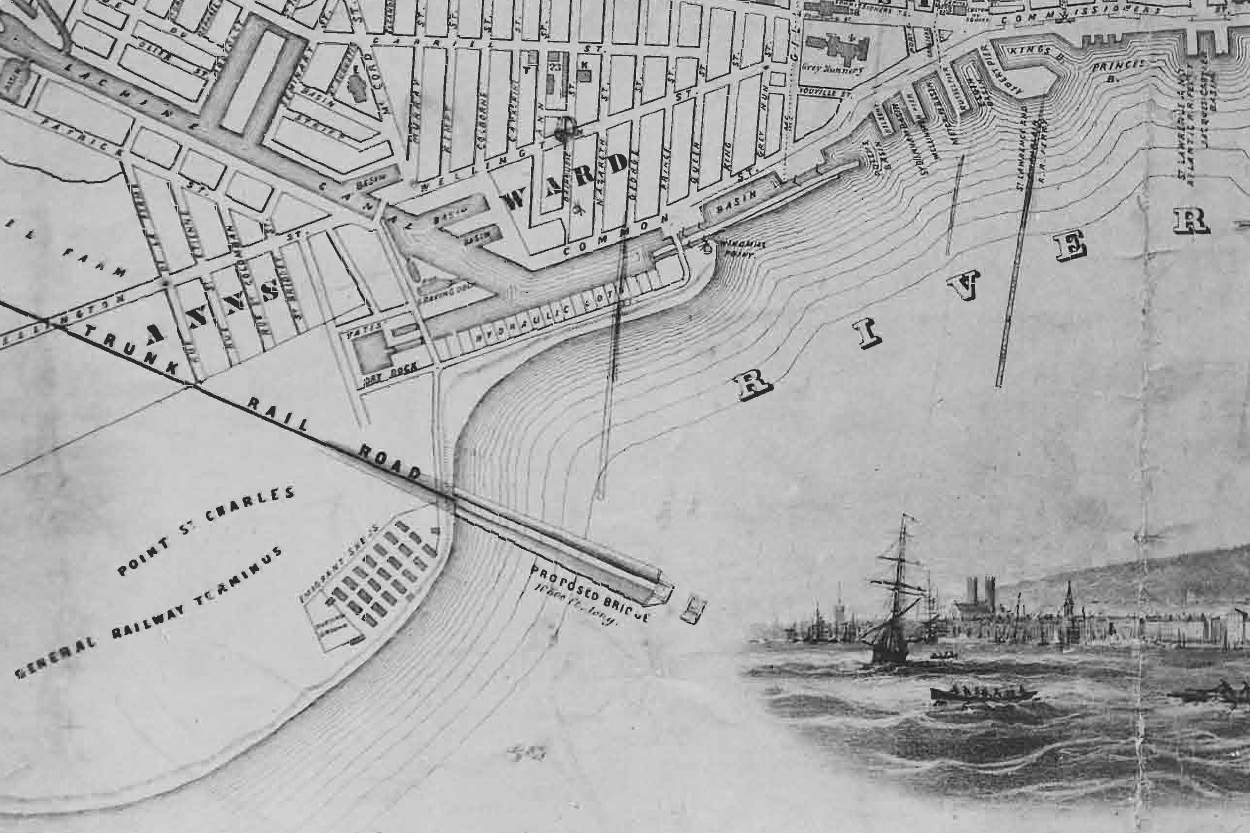

Wooden huts were built along the St. Lawrence River to care for the thousands of sick people. J. Duncan, Montréal Archives, 1853

Wooden huts were built along the St. Lawrence River to care for the thousands of sick people. J. Duncan, Montréal Archives, 1853

Given the magnitude of the epidemic, the dead were buried anonymously in wooden coffins near the St. Lawrence River. “It wasn’t an organized cemetery as we know it,” says Elizabeth Boivin, the REM’s deputy director of environment. “The burials were carried out with care, but there were no markers to precisely delineate the cemetery. It’s even more difficult given that the site is largely covered by railway tracks and roads today.”

It was not until the Victoria Bridge was built in 1859 that a first tribute was paid to the deceased. During that construction, the workers discovered bone fragments and decided to install a monument in memory of the victims. The Black Rock was pulled from the river to mark the cemetery and avoid desecration.

The Black Rock was erected by workers during the construction of the Victoria Bridge. William Notman, McCord Museum, 1859

The Black Rock was erected by workers during the construction of the Victoria Bridge. William Notman, McCord Museum, 1859

The REM passes through history

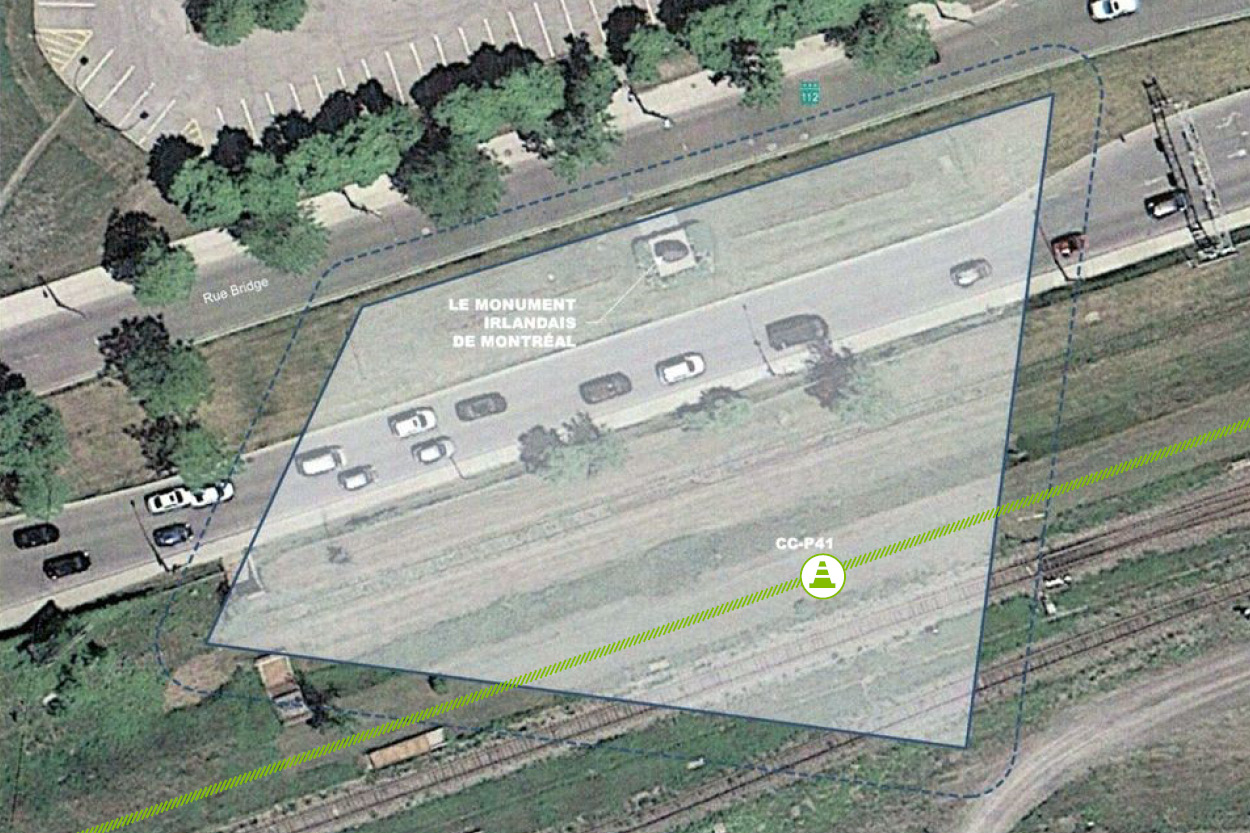

It was with this historical knowledge that began work in this area in 2019. From the maps and documents from that time, we knew it was likely that some of the REM work would occur on the Irish cemetery.

To minimize the impact, the design was specifically adapted in this area. “We agreed with the contractor to build a single pillar in this area (see dot in the diagram above), rather than the two we would normally put in place. The span between the pillars is therefore longer and we are using custom-made steel beams,” explains Elizabeth Boivin. “We also commissioned a firm to conduct archaeological excavations in the pillar’s caisson.”

This innovative approach was presented to and approved by the Ministère de la culture et des communications and Montréal’s Irish community. On June 12, 2019, a ceremony was held at the Black Rock to bless the soil before work began. Representatives of various religious groups, as well as the First Nations, attended the event.

Archaeological excavations

After the preparatory work, archaeological excavations were carried out at the site of the future pillar. This was a very meticulous undertaking: the excavations occurred within a diameter of three metres with little space to proceed, since the railway tracks were right next to it.

- First, the steel caisson was bored and anchored in the rock, at a depth of about 12 metres.

- The railway embankment (about five metres) was excavated to reach the level of the cemetery.

- The archaeologists entered the caisson in a cylindrical basket, custom-designed for the project. The basket had six removable plates that allowed the archaeologists to methodically carry out the excavations.

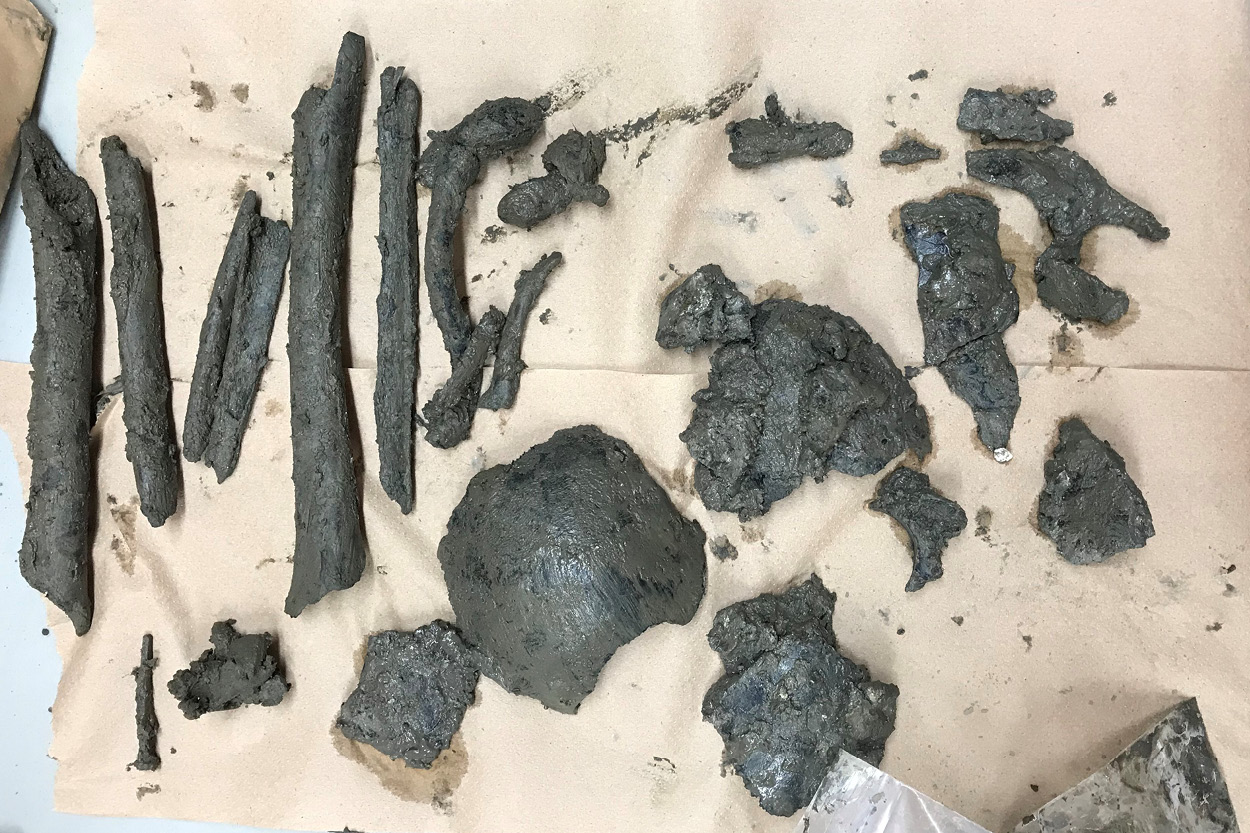

This research led to the discovery of the bones of 14 individuals. “The bone fragments are very well preserved in a layer of clay, despite the trains rolling above them,” says Boivin. “The specialized firm is currently cleaning, documenting and analyzing the graves. Given the position of the pillar and the historical information available to us, there is little doubt that these bones belong to Irish immigrants.”

Once the analyses have been completed, the bone fragments will be turned over to the Irish community, which is working with the City of Montréal and Hydro-Québec on creating a memorial park. It will be a way to pay tribute to the Irish people who have made such a substantial contribution to Montréal’s economic, social and cultural development.